Nigeria’s economic growth in the 21st century is one of the drivers of the ‘Africa Rising’ narrative… In April 2014, Nigeria became Africa’s largest economy, and the world’s 26th largest economy”

It is important that we try and understand the political economy of Nigeria. To do this we can learn from authors who may have a different view of the world, but can still provide important insights. Zainab, appears to have accepted the world view of the World Bank. She says that privatisation of Nitel was successful and opening up the Nigerian economy to free trade would be beneficial.

According to the figures Zainab provides (derived from Nigerian Bureau of Statistics and Central Bank of Nigeria data), the economy tripled in size between the years 1999 and 2015, this is confirmed by figures from the World Bank based on constant 2010 dollars (https://tinyurl.com/wgjvjst). But as importantly, this growth was based on sectors other than oil, so the value of manufacturing output increased by three and a half times and services by four times. As a result, the oil sector as a per centage of the GDP reduced from between a third and a half around 2000 to well less than 10 per cent by 2015.

In contrast to explaining the rate of Nigeria’s economic growth through the disadvantages of having natural resources, corruption or the positive role of the state, Zainab explains the intermittent economic growth through power relations within the ruling elite and international pressure resulting in an intermediate state. This is a state that falls between a predatory state based on fully rampant corruption (like some of the state governments in Nigeria) and a developmental state with optimal industrialisation (which Lagos State may have approached at its best). Despite this, it is clear to Zainab that state looting has been huge.

The end of the military era saw an elite bargain and the rotation of the presidency between the north and the south. But this omitted the poor majority who “made distributional demands on the state or found outlets in religious movements, armed groups or social media.” (page 26). So there were a series of general strikes and other major strikes over the last 20 years.

The results of economic growth over the last two decades are significant overall growth, but exports and government revenue have failed to diversify due to the failure of overall industrialisation. Zainab argues that internal settlements and external pressure were successful in the service sector, especially with the privatisation of the government telecommunications company, Nitel. However, they did not result in similar growth in the oil sector.

The contribution of the manufacturing sector may still be less than 10% of the economy, but it was the fastest growing sector over the 2011-2017 period and grew three and a half times over the period 1999 to 2017. This is faster than current growth rates in China.

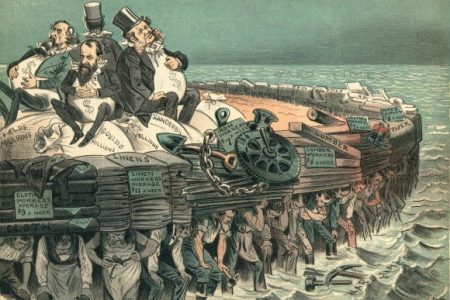

We can learn from her research, but we need to add in the impact of the working class and emphasise the role that this has played since the end of the military era. Zainab interviewed 120 people during 2014/5, but recognises that these are “elite interviews” (page 7) including business elites and senior government officials. The nearest Zainab gets to recognising the majority of the population is some interviews with “civil society actors” (page 7). So she presents a view of the economic history over the last 20 years from the viewpoint of the capitalist class (private and state). It is this “ruling elite and… domestic business class” that introduced neoliberal reforms over the last 20 years and it is this class that has greatly benefited from these reforms. In contrast, “Rising poverty and welfare concerns pitched Nigeria’s trade unions against market reforms” (page 7).

All this demonstrates that we have had significant economic growth over the last two decades but this has not enhanced human well-being for most of the population. The implications are that we should not worry so much about what government policies may further enhance future economic growth – but we should worry more about how the wealth is distributed. We need labour led development where collective action by the organised trade union movement wrestles improvements in their members economic conditions. Enhanced confidence from such struggles along with better organisation and experience by the trade unions may lead to further gains. The possibilities of moving beyond capitalism then open up from within the struggles against capital.